Some Thoughts on Words

Why the Chinese have no souls, Anglish is cool, and the Roman Empire destroyed European culture

As the subtitle suggests, these are some modest thoughts I had on language, the meaning of words, and what makes a word good.

A Chinese man I met recently, while discussing something with someone else, revealed to us listeners that the Chinese word for Computer is actually a composite word, 电脑 (pronounced Dian-Nao). Literally, this is actually two separate words 电, meaning electrical, and 脑, meaning brain that are stapled together in common usage, like the Germans love to do. It occurred to me much later after learning this neat factoid that describing a computer as an electrical brain suggests some very distinct connotations. What divides the human brain from a computer? The latter runs on electricity, no more and no less. The human brain, by implication, is just an organic computer, an idea many Western transhumanists believe in with no linguistic nudging. While not logically requiring this conclusion, this connotation lends itself to a materialist understanding of the human mind. Immaterial souls don’t exist, human cognition is just computers and logic gates and binary and stuff. I don’t know anything about the conceptual history of 电脑, but I suspect this connotation exists because the Chinese are a generally non-metaphysical race.

Compare to the “English” term, computer. Like a digger, a thing that digs, or a killer, a thing that kills, a computer is a thing (as designated by the -er) that computes. A very simple word. Connotations are simple as well. Computers are things that compute. There basically is nothing connoted. While one can say that brains are actually computers, nothing is implied by the term computer about the relationship between computers and brains. The term is instrumental and functional, it describes the function of the thing while making no connotations on the relationship between computers and any other concept.

But what is computing? Uh, I don’t know. As those with still functioning attention spans will have noticed and been mildly annoyed by, I put English in scare quotes in the above paragraph. This is because computer is not truly an English word, it is a Latin word. While most English speakers will know what computing means, nothing about that definition is implied by the term. This is not so in Latin. Much like with 电脑, compute is a composite term that combines the term ‘com-’, meaning with/together, with the term ‘putare’, meaning think about. A native Latin speaker, like the native Chinese speaker, can derive the meaning of the more complex word from the two words that compose it. The English speaker, who borrowed the word without borrowing the component words, cannot do this.

This is hardly a unique problem in English. Suicide, the English term for killing oneself, also literally means ‘to kill oneself’ in Latin. An English speaker who understands ‘kill’ and ‘oneself’ cannot use that knowledge to derive the meaning of suicide. The Latin speaker can. Ornithology combines a derivation of the Greek terms ‘ornith’, the term for bird, and ‘-ology’, the term for teaching. An English speaker who understands birds and teaching cannot derive the meaning of ornithology. A Greek speaker can. I leave as an exercise to the reader consideration of further examples.

With the pollution of all these loan words, an English speaker’s ability to think is weighed down by a bunch of foreign terms, each of which he has to memorize separately, instead of deriving them from a pool of relatively few building-block terms. Yet not only do these foreign words obstruct English thinking with regards to complex terms; the effect can even be felt with regards to simple Latin terms that have been imported wholesale into the English language. The use of the word ‘fetus’ is a good, if politically charged, example of this. In the debate over abortion (another Latinate complex word), those on the pro-abortion side often use the term ‘fetus’ instead of the term ‘baby’ to imply the unborn child is not fully human. This is despite the fact that the word ‘fetus’ is derived from Latin word for the offspring, a word that connotes a unity with the being from which one is springing off of. Bury this sleight of hand in an impossible to derive term from a foreign language and one can mislead the thinking of entire nations.

Preventing this confusion is one thing I love about the artificial language Anglish. Anglish works by replacing the many foreign derived words in the Modern English vocabulary with words derived from already used English terms. Alcoholic becomes Aleknight. Television becomes Farseer (Palantir in Tolkienian Elvish). Computer becomes Reckoner (from the now sadly antiquated word ‘reck’, best used, in my humble opinion, by Curtis Yarvin here). And so on.

While I have no proof, I suspect an awareness of this pollution of English by Latin through the Norman conquests was part of the reason why Tolkien despised the Roman Empire as the butcher of native cultures and thereby, the polluter of the ability of those cultures to think. As Tolkien says in Letter 77 of his collected Letters:

But one doesn't altogether wonder at a few smaller states still wanting to be 'neutral'; they are between the devil and the deep sea all right (and you can stick which D you like on to which side you like). However it's always been going on in different terms, and you and I belong to the everdefeated never altogether subdued side. I should have hated the Roman Empire in its day (as I do), and remained a patriotic Roman citizen, while preferring a free Gaul and seeing good in Carthaginians.

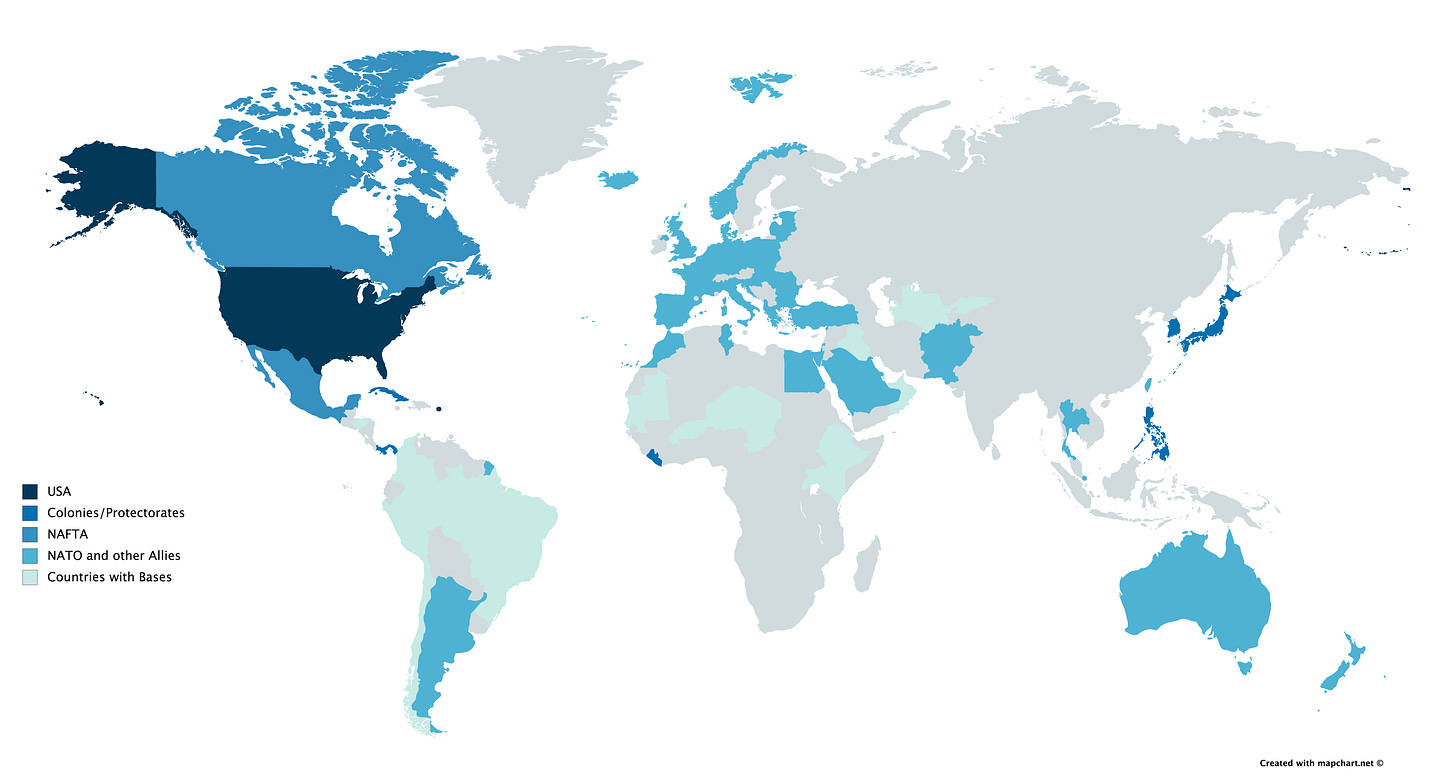

Truly, every European has already been colonized by a mighty culture, one whose Legionnaires planted their Imperial flag in our very speech. Even with the metaphysically misleading connotations of 电脑, I think this is why it is a superior term to ‘computer’. The meaning of the term is contained within the term itself. A Chinese who understands the building blocks can hear the word and immediately figure out what it means.

If only it lacked the misleading metaphysical connotations, like the objectively perfect-in-every-way Anglish term ‘Reckoner’.

One reason why Chinese creates so many new compounds is that every character has its meaning as well as its sound, so the importation of too many purely phonetic loanwords (like 卡哇伊 ka-wa-yi, kawaii, from Japanese) threatens to turn the whole language into gobbledygook. That is admittedly not the whole story, since Japanese has Chinese characters and yet shows the opposite tendency of high receptivity to loanwords, and had more inclination to create compounds in the Chinese style before the American conquest.

I don't know German, but I remember reading that compound words like Augenblick for "moment" were established over Latinate equivalents by early language purists who wanted to reduce the number of loanwords. Unfortunately I think that ship has sailed for English; the middle-to-upper reaches of the old language, where you would find relatively abstract words like niedþearflic ("need-tharve-like") for "necessary" and forþgewitenness ("forth-aweeten-ness") for "past", have been cut off just like the Anglo-Saxon nobility after the Norman Conquest. Anglish is fun as long as no-one is actually trying to force its prescriptivism on anyone.

Yet there is, I think, a way to restore something of Old English to the modern language, via the creation of an archaizing poetic language on the basis of the 'alliterative' (stave-rhyming) meter. This meter is 1) taken from Anglo-Saxon and non-Chaucerian models (thus induces us to read old texts and pick up old words), 2) based on a tight rhythm of two strong stresses per half-line (thus does not tolerate much Latinate longwindedness) and 3) ornamented by the chime of initial-sounds in stressed syllables of words (thus leads to a constant search for functional synonyms that dredges up many old words). More deeply, since it is a very archaic form imported into a modern context, it can carry along with it a kind of "perennialist" language-mindset that expresses modern phenomena through analogies with those of the past. Phrases and proverbs created in this elevated form could simply trickle down into normal speech, much as bits and pieces of Classical Chinese permeate modern vernacular Chinese and Japanese by way of the idioms known as chengyu/yojijukugo.

Really like this piece. Makes me think about how Sicilian and Italian used to be different languages. I wonder how Romance languages split to change optimism or views on different topics